Video/Blog: 10 Reasons Why Classroom Math Is Still Hard (in 2025)

Table of Contents

It’s a numbers game

You just don’t have enough time

It may not be difficult, just rare

Oftentimes it just becomes more familiar

You’re not cheating enough

Formulas are often the end of learning

Sometimes your teacher doesn’t know the answer

Historical context is often omitted

Mastery requires multiple cycles of learning

Math is human and humans are messy

Bonus

Here are ten reasons why classroom math might seem more difficult than it actually is.

Reason #1

It’s a numbers game

Silly math pun aside, what separates top students from the average students is not IQ or innate math ability — it’s more often than not time spent doing math.

Every student enters a classroom with varying levels of support. Some students have private tutors, attend after-school math programs, host math clubs, enroll in summer intensive programs, and may even have parents who are mathematicians, physicists, and engineers. By the time students enter their junior and senior year of high school, the difference in hours spent doing math can be in the hundreds if not thousands of hours.

I’ve personally seen students do summer intensive programs from 9am to 5pm, 5 days a week, for 4-6 weeks prepping for a single standardized test (ACT/SAT). Some students have completed entire two-year math curriculums before the first day of class. And prep for junior and senior year classes can begin as early as 7th or 8th grade.

And these students can still end up in classes right along side you. And the end result is that you may see a fellow classmate “cruising” through their math courses with little to no effort. You might assume that these students are math geniuses or born with the “math gene” when in reality it’s a lot of extra hours, big support systems, and sometimes a really large head start.

You will feel perpetually behind if you compare yourself to these students. It’s much more productive to aspire to be like the A students who are just putting in time within the limits of that class and who may not have all of that extra experience under their belt.

A good teacher will make sure that you as a student of average capability can get an A with a sufficient amount of work (no summer intensive classes required).

There are two ways to do great mathematics. The first is to be smarter than everybody else. The second way is to be stupider than everybody else — but persistent.

— Raoul Bott, Hungarian-American mathematician

Do not worry about your difficulties in mathematics; I can assure you that mine are still greater.

— Albert Einstein

Reason #2

You just don’t have enough time

On average as you move through middle school, high school, and college you will will likely have, on averge, six other classes vying for you time and attention.

Out of all the extracurriculars, advanced placement classes, sports, part-time jobs, and life in general; math is going to be a very small piece.

It may feel unsatisfying but you will leave every math class you take in high school and college feeling like you have a surface level understanding of the content. Yes, even if you get straight A’s. And that feeling will only be more exaggerated if you get B’s or C’s. And that’s ok. We’ll discuss why this happens in Reason #4, #6, #8, and #9.

Classes at the middle school to college level are often just a brief introduction to the material. 99.9% of students after they graduate high school and college will never really see math again in any really large way. Most math teachers, myself included, hardly ever see math in their everyday lives.

The most important thing to take away from your math classes is the ‘mathematical mind’ or the ‘mathematical approach’ and we’ll talk about that more in Reason #6.

The only way to learn mathematics is to do mathematics.

– Paul Hamos

One enters the first room of the mansion and it's dark. Completely dark. One stumbles around bumping into the furniture but gradually you learn where each piece of furniture is. Finally, after six months or so, you find the light switch, you turn it on, and suddenly it's all illuminated. You can see exactly where you were. Then you move into the next room and spend another six months in the dark.

— Andrew John Wiles

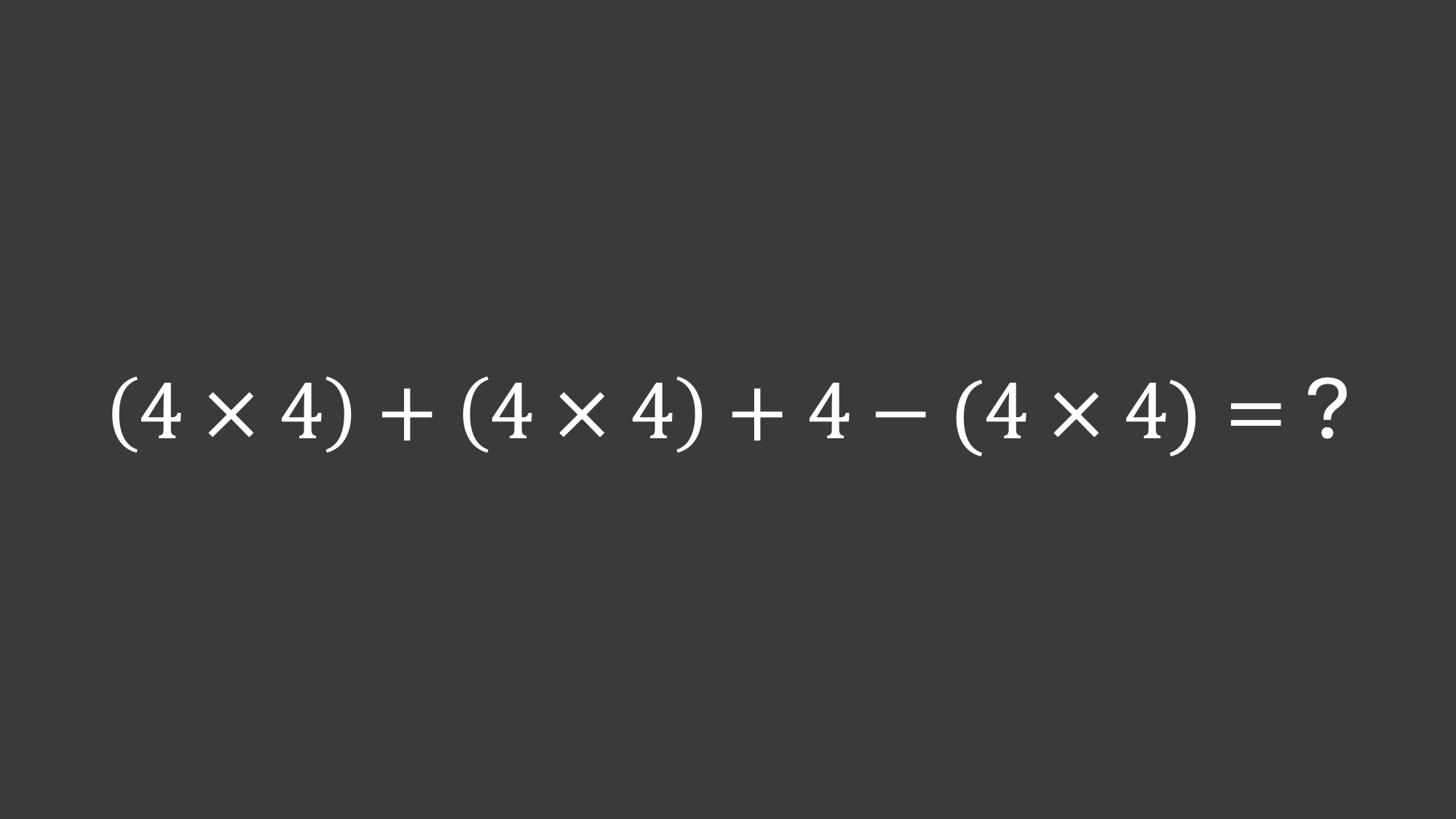

Reason #3

It may not be difficult, just rare

As you move through your math classes, you will see a lot of questions that claim to test your math ability, but, in fact, say very little about your math skill.

Solution can be found here

The math that we see in a question like this just doesn’t show up in any math classes (at least not after the 3rd or 4th grade) and certainly not in real life.

Math is a language and when we use a language we try to communicate as explicitly as possible and for this math expression, we could just add in some “math punctuation”:

Much better, right? And if this question seems too simple, we can increase the difficulty. How about this one?

You’re feeling just a bit uncertain right?

Even if you’ve completed a Calculus class, you might be now wondering if the order of operations is right to left or left to right. It’s just a skill that gets used so infrequently in later classes.

And contrived questions like these pop up in all sorts of ways in math classes from elementary school all the way up to college.

Questions like these can make you feel perpetually unskilled in math and even if you complete them, it can feel like your skills aren’t growing because you’ll never use those skills again in any future classes.

There’s also this now infamous SAT question:

Veritasium did a great video explaining this question: Youtube link

This question requires just a simple understanding of circle geometry and yet it stumped every single test taker, including the test makers who didn’t even include the correct answer (which is 4).

Questions like these that find their way into textbooks, homework, and tests will make your life more difficult as a student. And they can be a huge time sink. The best protection against this is teachers who meticulously review their curriculum. As a student, the best defense against these rare question types is cheating which we’ll discuss in Reason #5.

On a positive note, this does also make approaching classes much easier. Every math class has to have a specific subset of questions that are taught and tested. If not, the teacher could always find the most obscure and difficult questions in any topic to put on their tests and the class would be impossible to pass. A good teacher will define the scope of the course through their lectures and homework and the tests should more or less stay within that scope.

As you might imagine, for bad math classes, this will often not be the case!

Reason #4

Oftentimes it just becomes more familiar

If you’re reading this blog, then it’s likely that you have some degree of proficiency in English. It might even feel easy or effortless to use. Mathematics does feel that way the more you practice it but in some ways it never makes more sense. It just becomes more familiar.

Much in the same way that you probably cannot explain why “bear”, “beard”, and “fear” are all pronounced differently or why english speakers say “right on time” but “just in time”, math is equally confusing when you’re first starting out.

The perfectly sensible rules of English

Math is a human language and it has just as many quirks, oddities, and unexplainable rules as any other language.

For example, the negative one power can represent both the inverse and reciprocal operation:

The reciprocal of sine is cosecant.

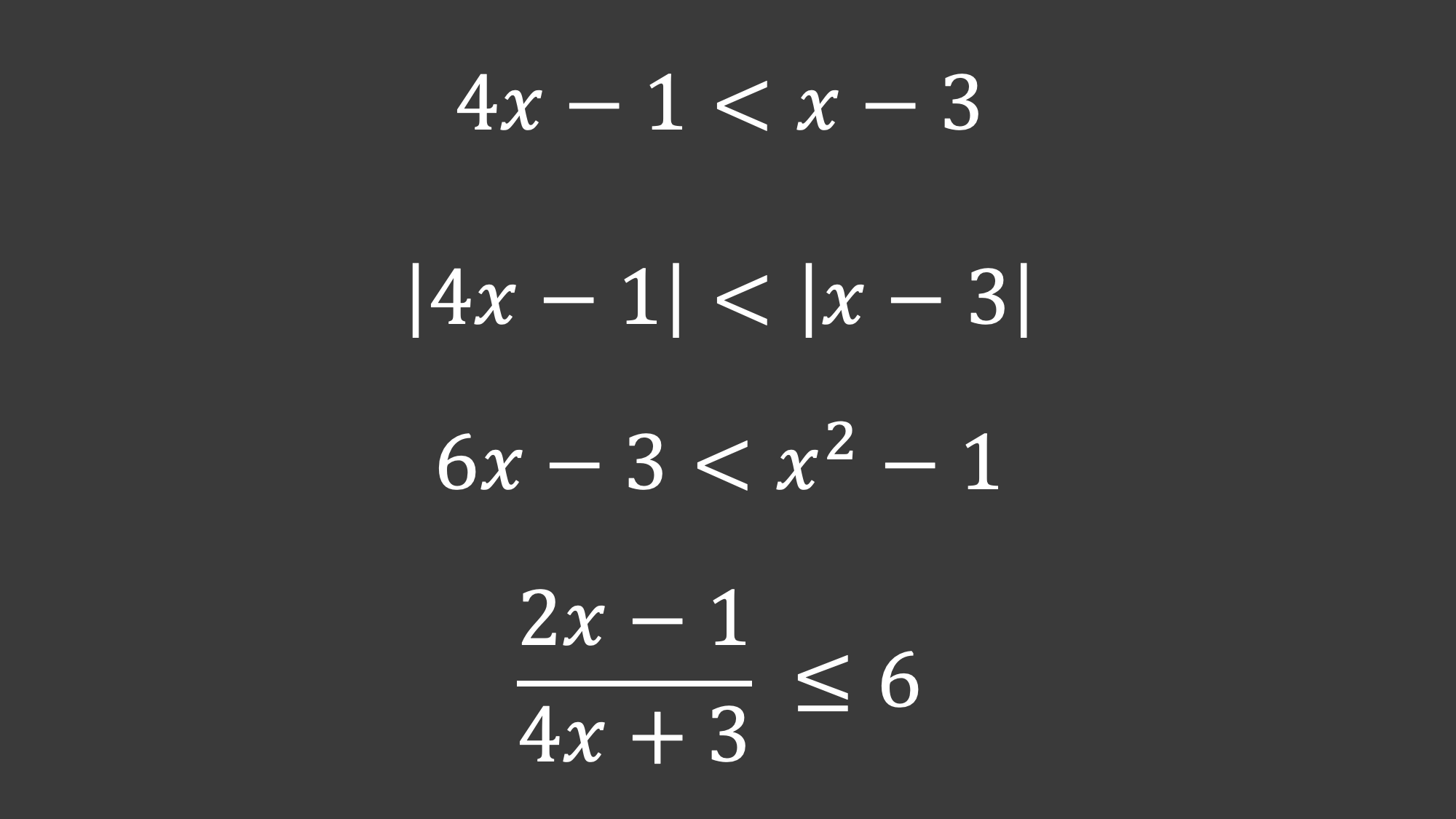

And then there are inequality equations with what feels like a million variations and hidden steps.

Algebra is an elegant language until it is not.

Unlike a normal algebra equation, you have to flip the direction of the inequality sometimes, quadratics and rational functions can’t be solved algebraically (only graphically), and absolute value functions require you to separate into two equations. And some solutions will be ‘false’ solutions that need to be double checked. It just goes on and on and on in this way.

Radians are another great example of this phenomenon. They become quite easy to use but they never really feel quite that intuitive.

When you’re in a math class, be ok with everything not making sense right away. Everyone else in the class (sometimes the teacher included) feels this exact same way.

One of the hardest parts of learning math is knowing when to ask more questions and dig deeper and when to just accept something and move on for the sake of time.

Note: There are also plenty of math concepts that are also waiting for a good math teacher to come along and explain in a clear, concise, and intuitive way. Try asking your teacher (or AI!) to explain the natural number “e” at a fifth grade level without using a banking analogy.

In mathematics you don't understand things. You just get used to them.

-Von Neumann

Mathematics is a language.

— Josiah Willard Gibbs, American scientist

Reason #5

You’re not cheating enough

As mentioned above, rare question types are going to be the bane of your existence as a student. And one of the best ways to keep these questions from taking up all of your study time is to cheat.

Many students when first starting out will spend too much time on their homework, working through every roadblock and dead-end in a question on their own as they work out a solution. This can take more than an hour for a single question if you’re not careful.

The secret to becoming good at math is not by solving every question on your own, but by working a huge volume of questions quickly. And the only way to do that is to “cheat”.

Every time you get stuck on a problem for more than a minute or five, you consult the solution manual and keep moving.

In a way, us humans are like Large Language Models (LLMs or gen AI) in that we develop our expertise by seeing thousands of questions and solutions. The more problems, solutions, and math topics we see, the larger our web of math understanding grows. It is then when we are presented with a new problem we have never met before, that we can pull from this vast database of experiences to give us some ideas of how to approach it.

And so if your goal is expertise, your momentum as a math student is one of the greatest assets you have to developing a vast, robust, and extensive web of knowledge and experience.

The good news for you is that building that level of skill is not required for any average math class. Learning a few question types, recognizing them, and improvising a little for small variations is all that’s required.

Your teacher may or may not subscribe to this “good cheating” way of learning and you may have to purchase your own solution manual or a 2nd textbook with a solution manual for practice.

It should also be noted that blindly copying down solutions will do very little to build your math skills and that your practice must always be active.

Reason #6

Formulas are often the end of learning, not the beginning

Oftentimes when you start a lesson or a chapter in a textbook you will be presented with a formula right away.

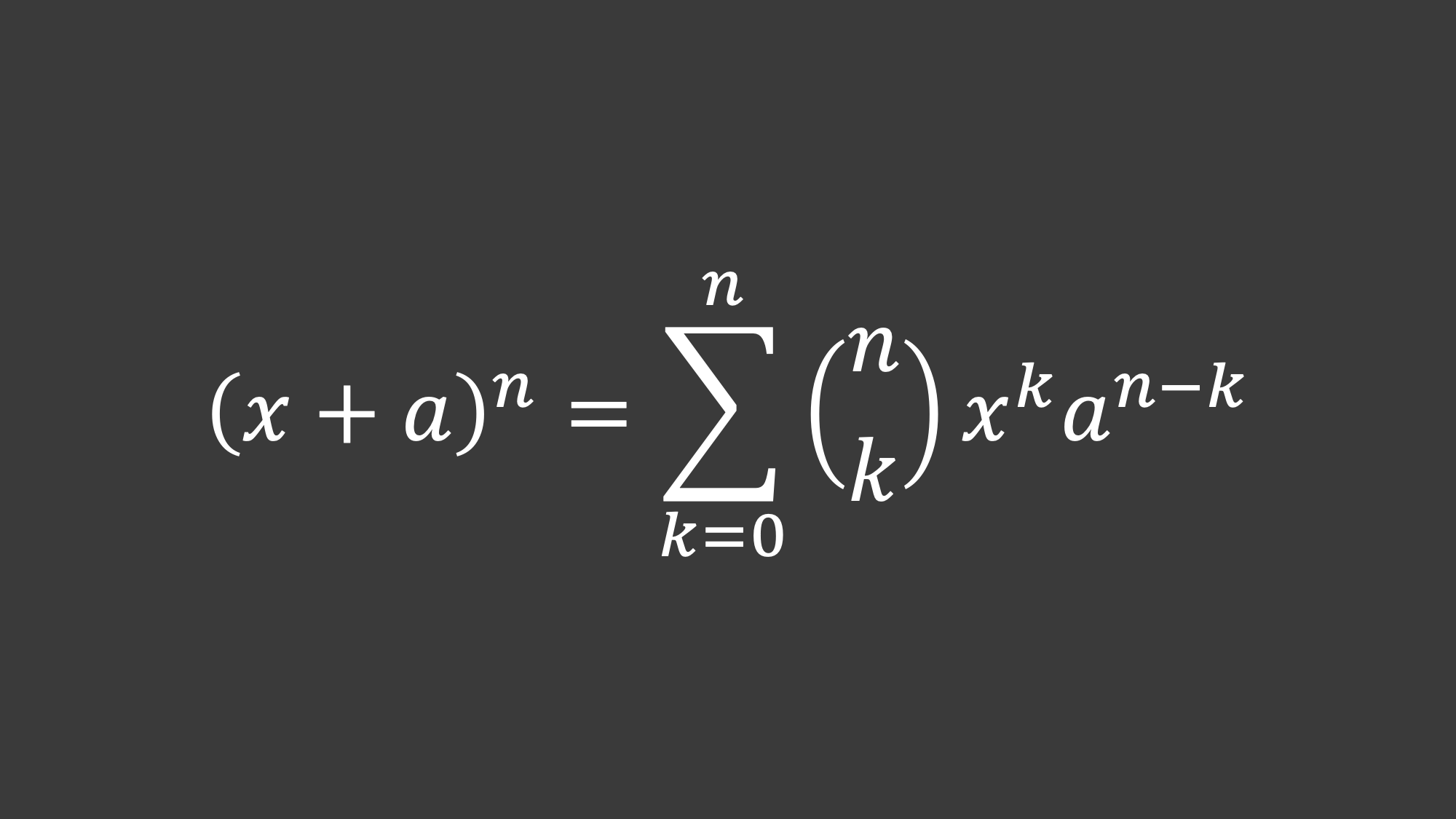

Let’s say it’s the Binomial Theorem:

If you understand this formula, it’s a really beautiful, succinct way to summarize everything to know about expanding binomials (even for negative, fractional, and negative fractional powers). You can see a full explanation of this formula in the video Newton’s Binomial Theorem. But would a beginner know that it’s just helping them see this simple pattern?

Oftentimes, no. Math textbooks and resources will often overwhelm you very quickly with a generalized formula for every conceivable case when you are just trying to get a “gist” of the topic when you’re first starting out.

This can make classes and self-study really challenging when it feels like all the content is being taught in reverse. Textbooks truly need a beginner version and a reference version.

—Start Rant

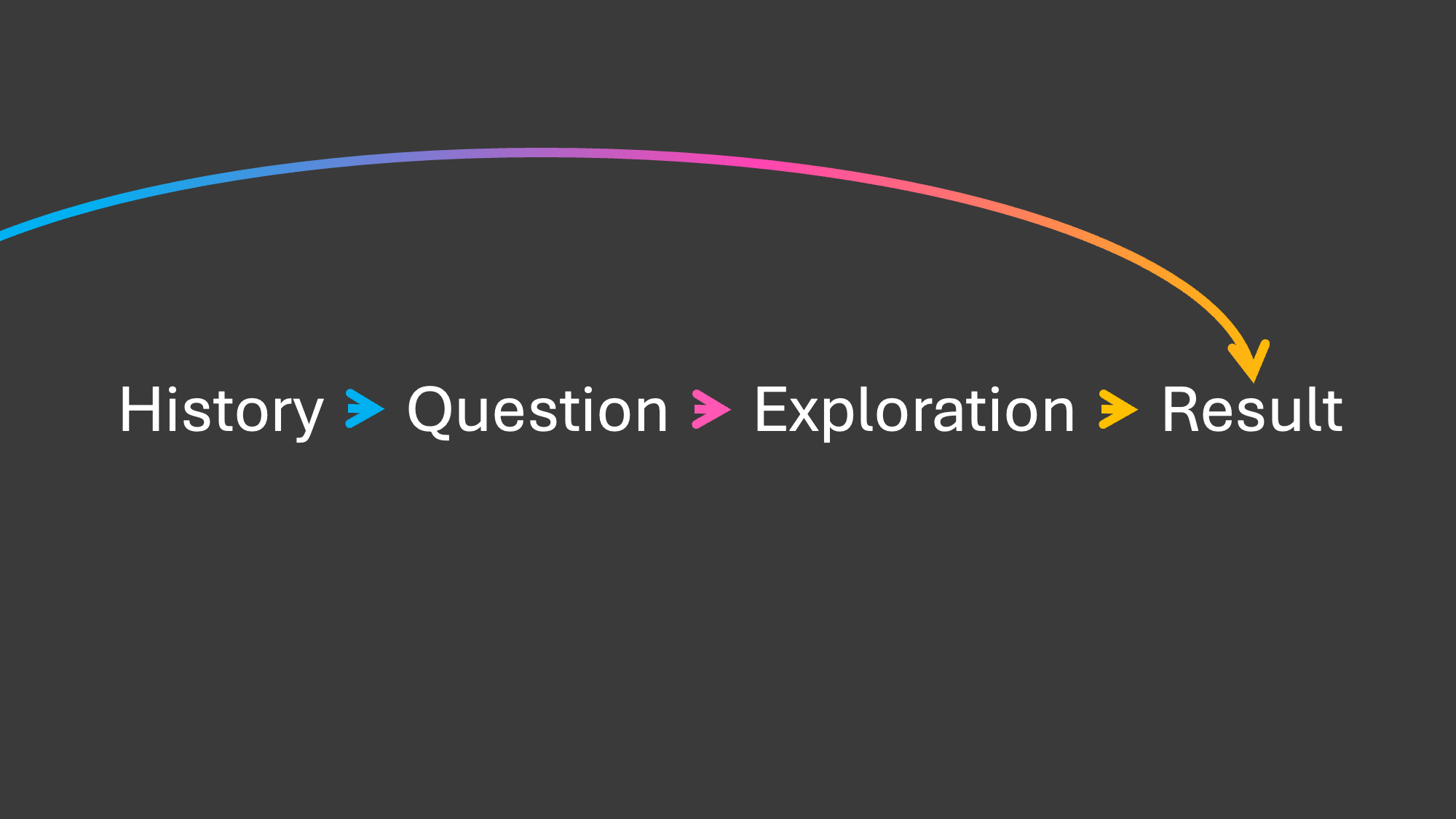

Math, at its core, is a way for us to observe the world or just math itself (like how binomials expand out in this beautiful repeating form), find patterns, and make predictions. It is in this process of observation, asking questions, and making predictions that you will develop your “mathematical mind” as a student.

There’s even one more step which we’ll discuss in Reason #8

Unfortunately, when there are time constraints in a class, the question and exploration phase of mathematics is often what is discarded first. This is one of the most worst mistakes of the modern math classroom and one of the reasons why you will often leave your classes feeling like you have a surface level understanding of the content.

—End Rant

A good teacher or resource will slowly build to the formula showing you lots of examples and context first. A good teacher will sacrifice correctness for simplicity. A good teacher will lie, focusing on helping you develop a solid intuition for the content before burdening you with every minor detail of the concept.

Just know that understanding comes first, rigor and precision comes last — and is usually seen as a sign of mastery.

As a student, don’t be pressured into deciphering a cryptic math formula from a dusty old textbook. It oftentimes is not the best way to learn content. And as we discussed previously there is just so much content to learn.

Find as many resources as you can tailored for “kids” and “dummies”. Try to find interactive math lessons, videos, and material that will guide you, step by step, through the question and exploration phase of learning math. It will be a much better use of your time.

There's no sense in being precise when you don't even know what you're talking about.

— John von Neumann

Reason #7

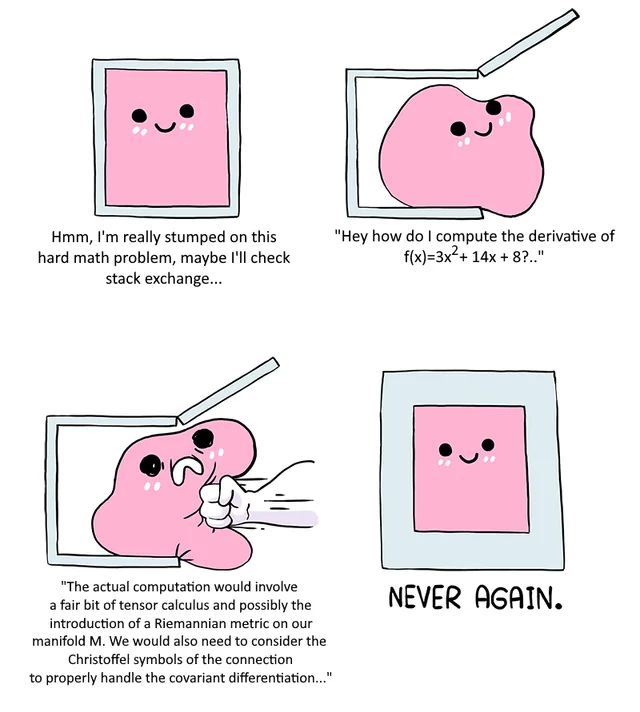

Sometimes your math teacher doesn’t know the answer

Ah, yes, the ole’ “the solution is left as an exercise to the reader” trick

Sometimes us teachers don’t know what we’re talking about. It might seem surprising that someone with 10 or 20 years of teaching under their belt is struggling to explain a fourth grade math problem to you, but as we saw previously, every math topic can be made infinitely difficult through rare question types.

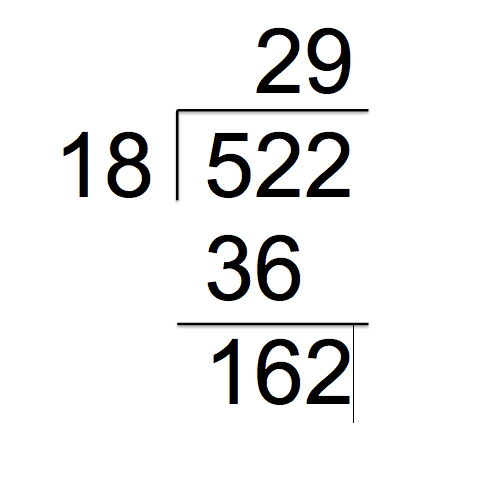

For example, remember the algorithm for long division?

Not too bad, right? How about with decimals?

4.16 ÷ 0.8

Yep, you guessed it. It requires an additional step before solving. Do you remember what the trick is?

And this happens across all of math from elementary school all the way up to college level math. Every single problem and problem variation requires you to learn and remember all of the solution steps. That’s an infinite amount of math to learn and retain.

So maybe your teacher forgot the method. Maybe they’re one of the 10,000 that just never encountered it through random chance. Maybe it’s been a long day. Maybe the problem seems simple and their ego won’t let them admit they can’t figure it out right then and there. But whatever the case may be, your teacher should follow up after class or in the next lesson with a correct solution.

As a student, seeing your teacher’s knowledge gaps is a great way to see that no matter how much math you learn, there will always be a simple math question that can come along and stump you. It’s a great reminder that no matter your level of math skill, you will never stop feeling like a beginner.

A good teacher will admit to these knowledge gaps and ensure that content does not show up in homework or tests without them addressing it first.

And as always, for a bad math class, this will often not be the case.

Answer: You have to multiply both numbers by 10 or 100 to remove the decimal from one or both numbers.

I realized with some relief that the people I supposed could solve every math problem were, in fact, often struggling.

— Sarah Flannery with David Flannery, In Code: A Mathematical Journey

Reason #8

Math classes often omit historical context

As we saw previously in Reason #6, the most important part of learning math, the question and exploration phase can often be let off when there are time constrains in a math class.

But another absolutely crucial part of mathematics is the historical context: all of the mathematicians who came before us and the context of their time periods that led to the math being discovered/invented as we use and teach it today.

Math history is even more absent in most math classes than any other step

Unfortunately, historical context is another big step in the process of learning math that often gets omitted when there is limited time.

For example, logarithms were initially invented by mathematicians to help with really large calculations before the invention of the computer. Nowadays we have calculators and just use logarithms to do the inverse of exponents:

When presented with a choice of how to spend an hour of education either 1)helping students understand the historical context or 2) doing practice to help students understand the concept and use the math — the latter is often chosen.

Another great example of this is how the order in which Calculus was discovered is quite different than the order in which it is taught today:

Math history is an absolutely fascinating topic but it usually doesn’t fit within the limited time of a standard math class.

As a student you have to accept that the math history will not always make the math concepts easier to understand and oftentimes the math history required to explain the topic can exceed the scope of the course (for example, needing calculus to explain why we need radians in a trig class). This does not mean that the concepts are impossible to understand.

As a student, you will likely not see the historical context in many of your classes and this will make math appear harder and less approachable than it actually is. This is a huge problem with math education at the moment.

In the meantime, wonderful YouTube videos like the ones linked above and math history books will be your best resources for filling in the gaps.

This will, again, be another reason why when you leave your math classes, you will feel like you have a surface level understanding of the topic.

Mathematics is as much an aspect of culture as it is a collection of algorithms.

— Carl Benjamin Boyer

Reason #9

Mastery requires multiple cycles of learning

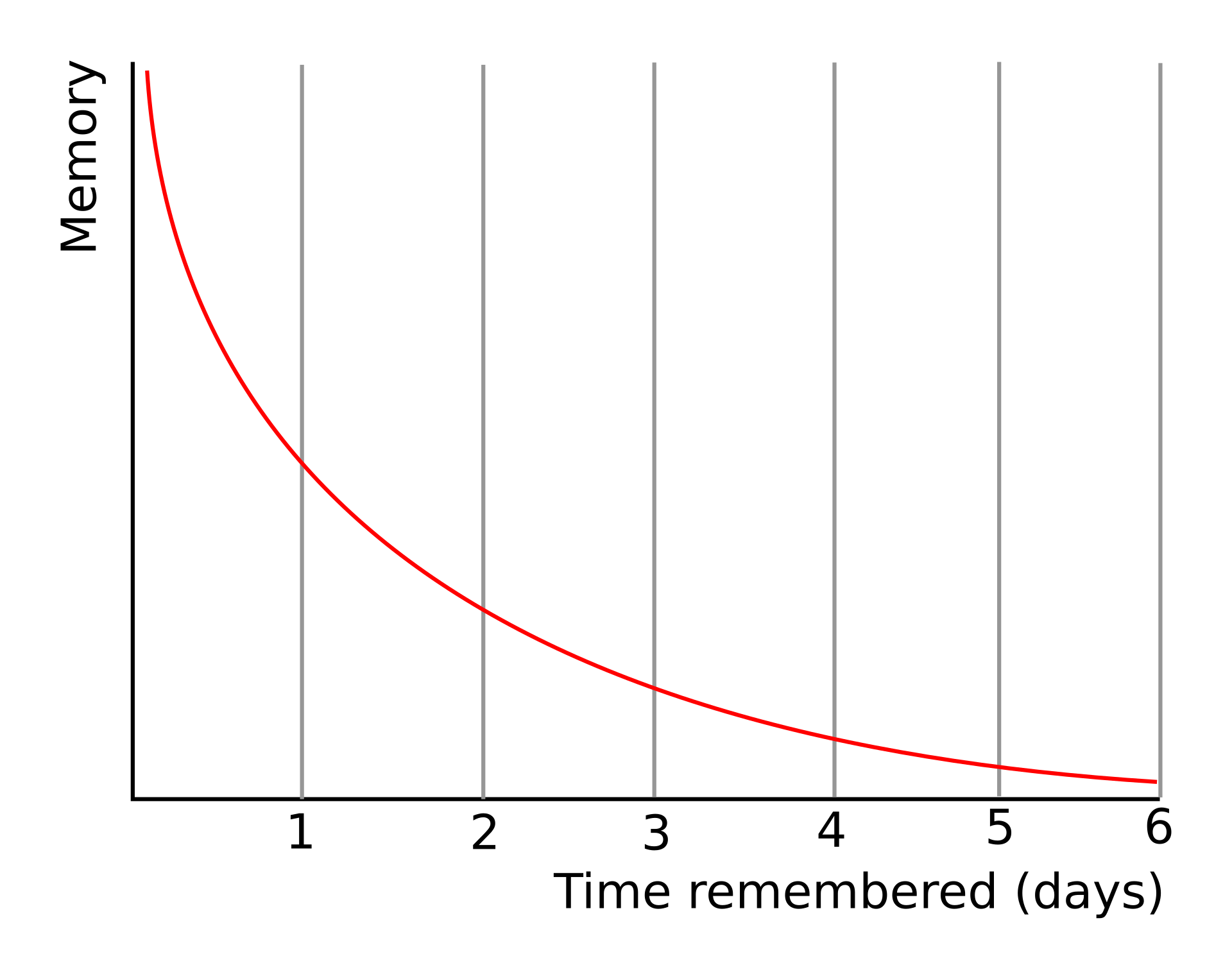

Here’s the forgetting curve.

This is also known as the Ebbinghaus' forgetting curve.

Memory fades exponentially with time (you forget the most on the first day and a little bit less with each passing day) until you eventually forget something entirely.

If you recall the original piece of information on the next day (or any later day), the forgetting curve restarts and you forget the piece of information more slowly (your memory lasts longer).

Spaced at just the right intervals of recall, you can very efficiently put lots of information into your long term memory very quickly. This is known as spaced repetition and there are a multitude of online resources to learn more about it. When studying consistently, you will do a lot of forgetting and repeat a lot of mistakes. Do your best to embrace forgetting and failure as a crucial part of learning.

Parallel to this process is another that you’ll pass through which is the concept of cycles of learning.

In an average class students get about one pass through the content with their primary teacher.

This will be yet another reason why you will often leave classes feeling like you have just a surface level understanding of the material.

Top-performing students can have up to three or four passes through the content. These students will often self-teach from a textbook and/or online, learn the content in class, learn the content a third time with a tutor or during a summer class, and in some cases experience a fourth cycle by teaching another student (perhaps using the Feynman technique).

Each cycle of learning often contains a unique perspective on the topic, different notational use, and slight variations in the homework sets which builds a very deep, very robust understanding of the topic.

Does the average student need more than one cycle of learning? Usually no. As mentioned in Reason #2, most classrooms and students won’t have the time to do so. Instead you’ll revisit these topics in future classes most times. But very often you may find that some of your skill areas are underdeveloped and need additional cycles of learning.

Success is a lousy teacher.

— Bill Gates

An expert is a person who has made all the mistakes that can be made in a very narrow field.

— Niels Bohr

Reason #10

Math is human and humans are messy

Mathematics is often idealized as a domain of pure objectivity, where logic and reason reign supreme, unencumbered by the messy complexities and biases of human nature. And it is a noble and valuable pursuit of those things.

But as math history has shown, it is still very much a pursuit, one filled with century after century of humans across every continent fighting to make their ideas heard, with no shortage of drama, intrigue, heresy, clashing personalities, and foundational mistakes.

Even math’s favorite celebrity, pi, is wrong.

And a little bit of that drama and humanness will make it’s way into every one of the classrooms you enter.

The first human that will make learning difficult for you is yourself. Technical fields make everyone who participates in them quite self-conscious about their intelligence and self-worth. How you label and view yourself as a learner, is crucial to your success.

Secondly, you’ll have to deal with the judgements and complexities of others. When you realize that others are struggling just as much as you are with the math concepts and their own self-doubt, it makes it much easier to protect yourself from shame or unhelpful criticism directed towards you.

If anyone tries to embarrass you for asking questions, answering questions incorrectly, or generally trying to learn and better yourself—just remember that it is a statement of their character, not yours. People are only as kind to you as they are to themselves.

Thirdly, you’ll have to deal with the realities of math culture. Math is often a boys’ club and can be very competitive. Students with large support systems (see reason #1) and big head starts may not always disclose their advantages.

The “positive” stereotype of “Asians are good at math” can put additional pressure on high-performing Asian students to maintain appearances. Underperforming Asian students can feel even further left behind than the average underperforming student.

Women and minorities are underrepresented in math (and STEM generally) and that’s even more true within math history.

Many teachers, textbooks, and resources will sacrifice simplicity for sounding smart leaving most students completely confused.

A student’s worst fate (Source)

Creating high level math learning resources can often be a way for a mathematician to show off their skill and proficiency.

But, making learning accessible is, in fact, quite at odds with feeling smart. The best explanations you can give will often leave you wondering why it took you so long to learn it in the first place.

To you, as someone who understands a topic, it might even feel silly or stupid to break content down into such small steps. But to a new math student, taking their first steps into a topic, it can make a world of difference.

At the end of the day, math is a beautiful, creative, and really rewarding field of study and we should be collectively encouraging as many people to take interest as possible. And that won’t happen until we can take a lighter, more fun, and more relaxed approach to who can participate and contribute.

——

In recent news, two high schoolers were able to discover a new proof for the Pythagorean Theorem.

Another teen recently refuted the Mizohata-Takeuchi conjecture.

Science is not a boy's game, it's not a girl's game. It's everyone's game.

— Nichelle Nichols, NASA Ambassador & Star Trek actress

Bonus Reason #11

You just might not like math and/or be good at it

But hopefully you can rule out the above reasons before you come to any conclusions that you dislike or hate the topic.

And, of course, it should be noted that some students will have learning differences like dyscalculia (dys-cal-KYOO-lee-uh) ( affecting around 5% of students) which will make the study of math more difficult than for the average student.

At the end of the day, the study of mathematics is just one out of a million ways to be smart and creative and you just might find your passion in studying a different language and that’s perfectly ok too.

Whether it’s in a math class or after you gradate, hopefully wherever your interest eventually falls, you will at some point get to appreciate the beauty of the mathematical mind. That using these often abstract models to view the world, can be a really beautiful way to better understand yourself and the world around you.

I had a polynomial once. My doctor removed it.

― Michael Grant, Gone

Back to Top